- Name means: “Wonderfully Terrible Hand”

- Height: 3-6 meters

- Weight: 9 tons

- Length: 13 meters

- Region: Gobi Desert, Mongolia

|

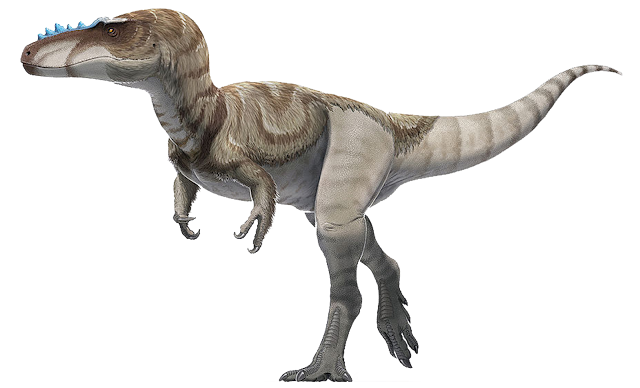

| (Copyright: Andrey Atuchin) |

One of arguably the oddest dinosaur

discoveries to date, Deinocheirus, has

been an enigma for over 50 years. Ever since its discovery Deinocheirus, which translates from Latin to “Terrible Hand”, has

captured the imagination of those with the right resources to know about it.

Despite its enigmatic nature in the fossil record, Paleontologists were finally able

to put the mystery of how the animal looked to rest in 2014.

|

| (Copyright: Public Domain Wikipedia) |

The first fossils of Deinocheirus consisted of the massive forearms (only missing the claws on the right hand), the complete

shoulder girdle, three dorsal vertebrae, five ribs, and the gastralia (commonly

referred to as belly ribs). Polish Paleontologist, Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska, found

these remains in the Nemegt Formation of the Gobi Desert, Mongolia on July

ninth 1965. Zofia, along with Paleontologist Rinchen Barsbold, were part of the

1963–1965 Polish-Mongolian paleontological expeditions when they found the

remains. The arms were classified as a Theropod

dinosaur, and considering the lack of extraneous material, the scientists had no

idea as to what the animal looked like until the year 2012. In 2012,

Phil R. Bell, Philip J. Currie, and Yuong-Nam Lee issued their findings of new

Deinocheirus material. These scientists found more gastralia fossils in the

same dig site of the prior team. What they found explained the scarcity of

material from the dig site. They found bite marks on the gastralia that matched

the teeth of the Tyrannosauid, Tarbosaurus,

with which Deinocheirus shared its

ecosystem. Then in 2013, Lee, Barsbold, Currie, and colleagues announced the

discovery of two new Deinocheirus

specimens at the annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology conference. This

find gave great insight into what the animal looked like and where the animal

fit in, phylogenetically. Due to fossil poachers, much of the identifiable parts

of the skeletons were gone; the heads, feet, and hands were all stolen. A short

time later, word of the skull and hands making their way to the fossil black

market helped the European museum acquire them. This skull solidified not

only the identity of this bizarre dinosaur, but also nailed the final nail in

the coffin to the secret of Deinocheirus.

|

| (Copyright: Public Domain: Wikipedia) |

|

| (Copyright: Public Domain Wikipedia) |

Deinocheirus

is known by only one species, coined Mirificus, which translates to

‘wonderful’. It is now known that Deinocheirus

was a giant amongst Ornithomimids. It

towered at a height of 3.5 to 6 meters and measured a length of 11 meters, and

could have weighed as much as 6 tons; Deinocheirus

is the largest example of Ornithomimosauria

that currently exists. The fossils of Deinocheirus

suggest omnivory, due to evidence of piscivory and herbivory found in

its stomach. Gastroliths (stones swallowed to aid in

digestion) and fish scales were found in the stomach cavity of the skeleton and

points to a varied diet of plants, fish, and probably other types of vegetation

like fruit. Deinocheirus lived during the Late Campanian/Early Maastrichtian of

the Cretaceous Period of what is now Mongolia.

|

| (Copyright: Public Domain Wikipedia) |

Deinocheirus’ relatives are Garudimimus and Beishanlong. All three of these animals

make up their own family within Ornithomimosauria

and share the characteristics of a slower mode of life and a bulkier build than

most other Ornithomimids. Deinocheirus, being an omnivore, would

have had little competition from its contemporaries with the only exception

being Therizinosaurus; both shared

similar characteristics and were likely omnivorous.

Deinocheirus shared its ecosystem with a wide range of animals like

Tarbosaurus, Pinacosaurus, Saichania, Protoceratops, Oviraptor, Velociraptor,

and more. Evidence strongly suggests that the first specimen met its end from a

Tarbosaurus (a Mongolian relative of Tyrannosaurus) and, as such, must have

been a predator of Deinocheirus. Alioramus, another relative to Tyrannosaurus, may have preyed on Deinocheirus as well. Deinocheirus lived in a place that, at

the time, was home to vast swamps and river ways, which would have provided it

a niche that most other herbivores and even most carnivores had yet to adapt

to; Omnivory.

|

| (Copyright: Art belongs to Geocities) |

The Paleontologists that found Deinocheirus quickly determined it to be a

Theropod; however, what kind was

impossible to know. At the time, 1965, the scientists thought the arms

belonged to a massive carnivorous carnosaur-like animal. At this point in history, most carnivorous theropods were thrown together into one phylogenetic ‘unnatural’ grouping called Carnosauria

(This has since been revoked due to further variation amongst the Theropoda family tree). Deinocheirus became identified as something other than a carnivorous Theropod only after the gastralia material had been found. The discovery of Therizinosaurid

dinosaurs, like Nothronychus and Segnosaurus, made the possibility of herbivorous

theropods a reality. Paleontologists had been debating whether Deinocheirus was an Ornithomimid or a Therizinosaurid

until the latest skeletal discovery made the decision. Even though science knows more about

Deinocheirus than ever

before, aspects of its paleobiology and habits are still unknown and only more

material will unearth the secret of Mongolia.

|

| (Copyright: Art belongs to Geocities) |

|

| (Copyright: Scale belongs to PrehistoricWildlife) |

Works Cited

"Deinocheirus." Wikipedia.

Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 03 Nov. 2015.

Yong, Ed. "Deinocheirus Exposed: Meet

The Body Behind the Terrible Hand." Phenomena Deinocheirus Exposed Meet

The Body Behind the Terrible Hand Comments. National Geographic, 22 Oct. 2014.

Web. 03 Nov. 2015.

"Deinocheirus." Deinocheirus.

PrehistoricWildlife, n.d. Web. 03 Nov. 2015.

Perkins, Sid. "Fossils Reveal

'beer-bellied' Dinosaur." Nature.com. Nature Publishing Group, 22 Oct.

2014. Web. 03 Nov. 2015.