In Tyrannosaur evolution, there is a 20 million year gap in the early-mid Cretaceous that excludes evidence of how this group of animals achieved its large dominating size. When new organisms are uncovered that shed light on these kinds of ‘dark gaps’, they help to shed new light on the way a group of animals develops over time.

| ||

Material referred to Timurlengia

|

Timurlengia, coined in reference to the emperor Timurleng, became known in 1944. The original material, found in Uzbekistan, consisted of fragmentary bones and would remain in storage until a group of researchers uncovered a braincase in 2004; All of the fossils were again put into storage. Steve Brusatte analyzed the remains in 2014 and determined that the fossils suggested a unique genus. It was not until 2016 that Brusatte et al. coined the type specues Timurlengia euotica, euotica translating to “Well-eared”. In total, the material collected consist of; the right half of a braincase, right maxilla, left frontal bone, left quadrate, piece of a right dentary, a right articular with angular, front neck vertebra, rear neck vertebra, the neural arch of the front back vertebra, middle back vertebra, front tail vertebra, middle tail vertebra, rear tail vertebra, and a toe claw. All of these fossils were uncovered in the Bissekty Formation of the Kyzylkum Desert and date to the Turonian age of the early late Cretaceous period, approximately 90 million years ago.

References:

Lazaro, Enrico De. "Timurlengia Euotica: New Species of Tyrannosaur Discovered in Uzbekistan." Timurlengia Euotica: New Species of Tyrannosaur Discovered in Uzbekistan. Sic-news, 15 Mar. 2016. Web. 24 Mar. 2016. <http://www.sci-news.com/paleontology/timurlengia-euotica-new-species-tyrannosaur-uzbekistan-03702.html>.

Brusatte, Stephen L., Alexander Averianov, Hans-Dieter Sues, Amy Muir, and Ian B. Butler. "New Tyrannosaur from the Mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan Clarifies Evolution of Giant Body Sizes and Advanced Senses in Tyrant Dinosaurs." New Tyrannosaur from the Mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan Clarifies Evolution of Giant Body Sizes and Advanced Senses in Tyrant Dinosaurs. PNAS, n.d. Web. 24 Mar. 2016. <http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2016/03/08/1600140113>.

|

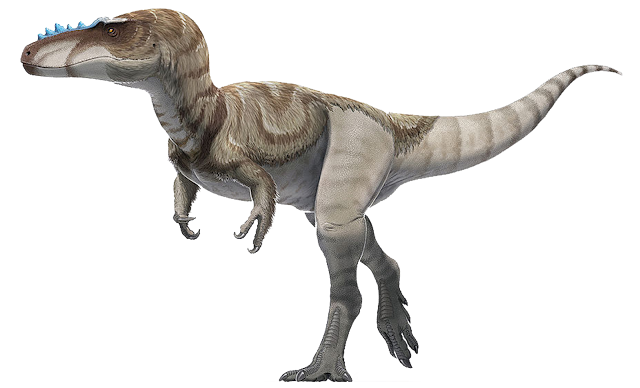

| Art and Copyright belongs to Fabrizio De Rossi |

Timurlengia shows characteristics of both early and later Tyrannosaurs; it had very well-developed sight, smell, hearing, and cognition reminiscent of the later Tyrannosaurs. The evidence of heightened senses but small size and slender snout suggest that Tyrannosaurs evolved their enormous size in a quick period of time. Timurlengia was an animal of around 9 to 12 feet in length with teeth designed for the rendering of flesh and senses developed for pursuit of fast-moving prey, like hadrosaurs.

|

| Art and Copyright belongs to James Kuether |

References:

Lazaro, Enrico De. "Timurlengia Euotica: New Species of Tyrannosaur Discovered in Uzbekistan." Timurlengia Euotica: New Species of Tyrannosaur Discovered in Uzbekistan. Sic-news, 15 Mar. 2016. Web. 24 Mar. 2016. <http://www.sci-news.com/paleontology/timurlengia-euotica-new-species-tyrannosaur-uzbekistan-03702.html>.

Brusatte, Stephen L., Alexander Averianov, Hans-Dieter Sues, Amy Muir, and Ian B. Butler. "New Tyrannosaur from the Mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan Clarifies Evolution of Giant Body Sizes and Advanced Senses in Tyrant Dinosaurs." New Tyrannosaur from the Mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan Clarifies Evolution of Giant Body Sizes and Advanced Senses in Tyrant Dinosaurs. PNAS, n.d. Web. 24 Mar. 2016. <http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2016/03/08/1600140113>.